All it took was a single paper boat to alter the course of the eight-year-old Erwin Dolera’s future. Nine and a half years ago, it seemed there was no way for his family to send him to school. At that time, a fatal landslide at the Payatas dumpsite in Quezon City deprived his family of their livelihood. His brother was killed in the tragedy. But with the help of a civic group that went to the Payatas slums, Erwin and 32 other children were able to convey their grievances and wishes to newly-installed President Gloria-Macapagal Arroyo.

In 2001, Pres. Arroyo promised to fulfill the dreams of Jason, Jomer, and Erwin (L-R), collectively known as the "Bangkang Papel boys." Now a 17-year-old Mass Communications junior, Erwin is a grateful beneficiary of President Arroyo's scholarship programs. Sophia Dedace, GMA News video grab

Dolera asked for the closure of the dumpsite, 10-year-old Jason Banogan asked for education, and 10-year-old Jomer Pabalan asked for a job for his father. They later scribbled their dreams on paper boats, which they left to drift on the Pasig River. Little did they know that Malacañang would get wind of the “Bangkang Papel" boys and choose them and their wishes to personify the President’s agenda in her first State of the Nation Address in July 2001. The boys were asked to stand and acknowledge the audience’s applause, creating a heart-warming tableau at the height of Arroyo’s popularity.

Nine years later The fate of the three boys is a mixed report card on the Arroyo government’s performance in education. Today, the 17-year-old Dolera is well on his way to fulfilling his dream of finishing college and getting his Mass Communications degree at a private university. Pabalan, for his part, is an information technology freshman in Rizal. Banogan, on the other hand, waived his government scholarship because he felt his privacy was being violated by the publicity of being a presidential poster boy. Dolera, however, remains grateful for the attention.

“Ang laking tulong talaga ng scholarship from Madame President. Namatay ang father ko noong 2007, ang mother ko namatay noong 2008. Ang ate ko na lang talaga ang bumubuhay sa amin. Kung wala ang scholarship, wala na rin akong kinabukasan," he said at his home in Lupang Pangako, Payatas. Beaming proudly, Dolera said he is not just an emblem of the President’s promises but proof of the President’s plans fulfilled – his schooling has been financed by the government since the 2001 SONA. He tells kids who feel hopeless:

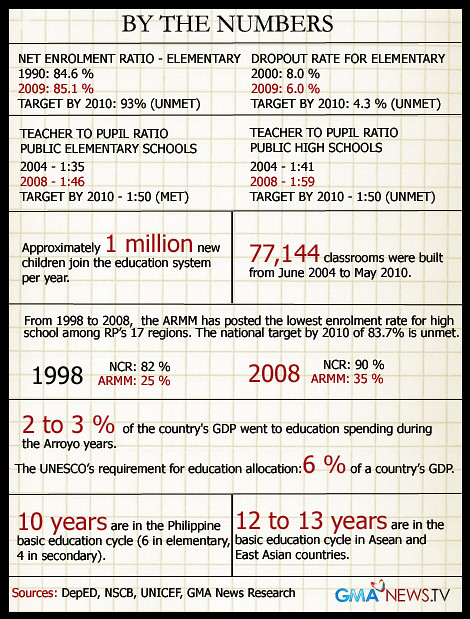

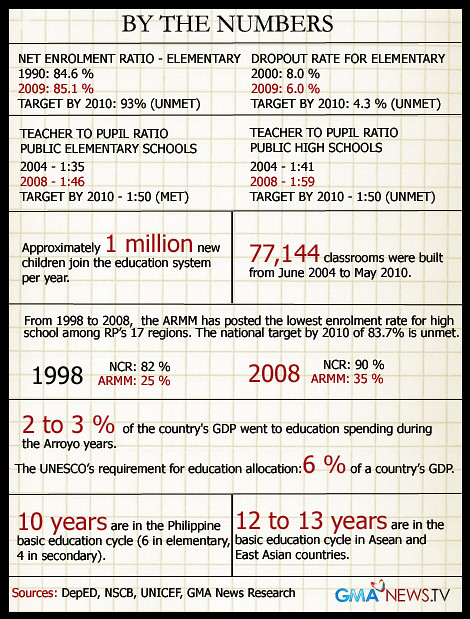

“Kapag iniisip nila na dahil sa sobrang kahirapan ay di na sila makakapag-aral, huwag mawalan ng panananmpalataya at magpursige lang. Gumawa nang mabuti para makahanap ng solusyon sa problema." By the numbers But not all children are as fortunate as Dolera and Pabalan. During President Arroyo’s administration, the “Bangkang Papel" boys are more the exception than the rule. The most recent Department of Education records show that out of 100 children who enter Grade 1, only 43 graduate from high school. Of this number, only 23 will enter college or pursue technical education. Of the college enrollees, only 14 will graduate. In her inaugural address in 2004, the President promised that “everyone of school age will be in school" when her term ends in 2010 — strong but believable words from a former economics professor with a doctoral degree. However, as of 2009, only 85.12 percent school-age children were in primary school. This is worse than the participation rate of 96.77 percent in 2001 when President Arroyo assumed office.

In the Philippines, GMANews.TV’s research shows that the Arroyo years were plagued by high dropout rates, declining enrolment, and the failure to reform the education sector. Data from the DepEd and the National Statistical Coordination Board showed that the dropout rate at the elementary level (6.0 percent for 2008) during the Arroyo administration is higher than the target of 4.4 percent.

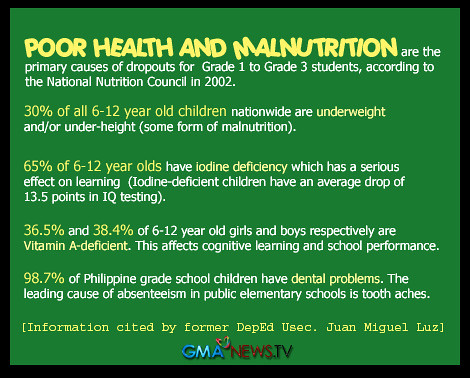

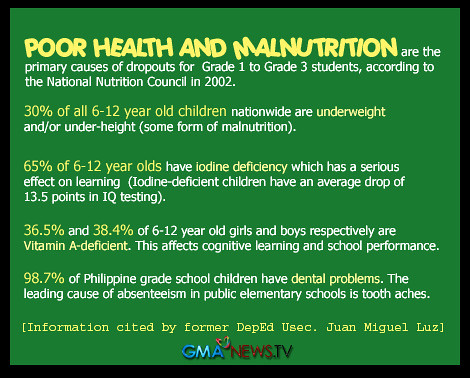

Drop-outs Ma. Lourdes de Vera-Mateo, Education chief of the United Nations Children’s Fund in the Philippines (UNICEF-Philippines), links higher dropouts to rising poverty levels in the Philippines: families have to meet their daily needs first before sending their children to school. Poverty also causes malnutrition, and an empty stomach prevents a child from going to school and also affects his cognitive development. “We have a lot of catching up to do in terms of ensuring the participation of children, especially the hard-to-reach ones. They are vulnerable to many risks, which prevent them from staying in school. We also know that before they can learn, we must ensure they are healthy so they are not at risk of dropping out," she said.

For those in higher primary grades or high school year levels, “boys are two to three times more likely to drop out or repeat because they are vulnerable to a wider range of hazards, including child labor and armed conflict. Sometimes, they are constricted to join armed movements especially in the provinces," she adds. The government’s Functional Literacy, Education, and Mass Media Survey (FLEMMS) in 2003 found out that of the 11.6 million children who were not attending school, 30 percent were not enrolled because they were working or looking for work, 22 percent lacked interest, while 20 percent could not afford it, even though public schools are supposed to be free.

Alternative learning modules

Kabuntalan, Maguindanao children leave their hand prints on a notebook to call attention to the dismal plight of their school. GMA News and Public Affairs will give the notebook to President-elect Aquino. GMA News and Public Affairs: Biyaheng Totoo

In the village of Matila in Kabuntalan, Maguindanao, students cross a crocodile-infested lake every day to reach their school – which has only one teacher earning one-fourth of the regular monthly salary allotted for public school teachers. Maguindanao became notorious last year for the Ampatuan massacre. For a long time, however, it has been one of the poorest provinces in the country. It also belongs to the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, the region with the lowest literacy rate in the Philippines.

Corruption by local kingpins also hampers the delivery of basic services, such as education. In rural areas, it has been common for children to leave their homes before daybreak because their schools are several kilometers away. Finishing college is a dream as distant as their school. For such far-flung areas, De Vera-Mateo recommended to the DepEd the use of alternative learning modules so that students who cannot adapt to department-imposed standards and the pace of a regular school year can still get basic education. “We are supporting the department in alternative delivery modules. The idea is to make the system more inclusive and flexible. Poor children in far-flung areas have difficulty in keeping with the school calendar and are more at risk of going to work early," she said. “That is why the government should invest in life skills-based modules, which are more appropriate in certain settings, such as those in hard-to-reach areas," De Vera-Mateo added. She added that the government must also focus on early childhood care and development – one of the areas being pioneered by UNICEF – to help form the cognitive brain development of children in pre-school years.

Millennium Development Goals The problems besetting Philippine education are best reflected by performance indicators of the Millennium Development Goals, targets set in 2000 by United Nations member states committed to work towards eliminating poverty by 2015. Among these goals is a pledge to achieve universal primary education.

Participation rate, also known as net enrolment rate, refers to the ratio of the enrolment for the age group corresponding to the official school age in the elementary or secondary level to the population of the same age group in a given year. The cohort survival rate is the proportion of Grade 1 enrollees who reach Grade 6. Completion rate, on the other hand, refers to the percentage of Grade 1 enrollees who finish grade school. Citing UN records, De Vera-Mateo says the goal of achieving universal primary education is the hardest to achieve in the Philippines. “We still have a long way to go," she said. The 2007 Philippine Midterm Progress Report on the MDGs also said there was “low probability" that the Philippines would achieve its goal on universal primary education by 2015.

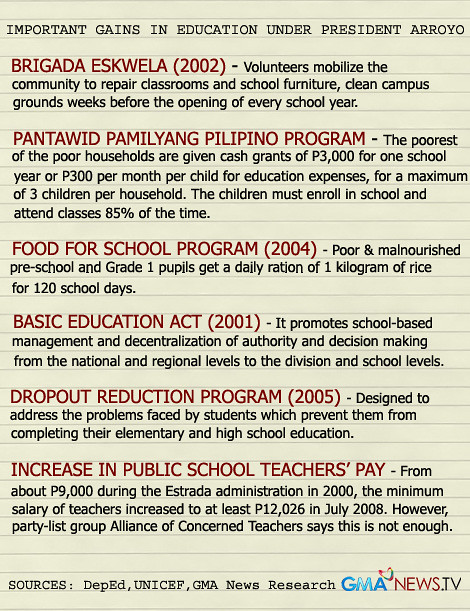

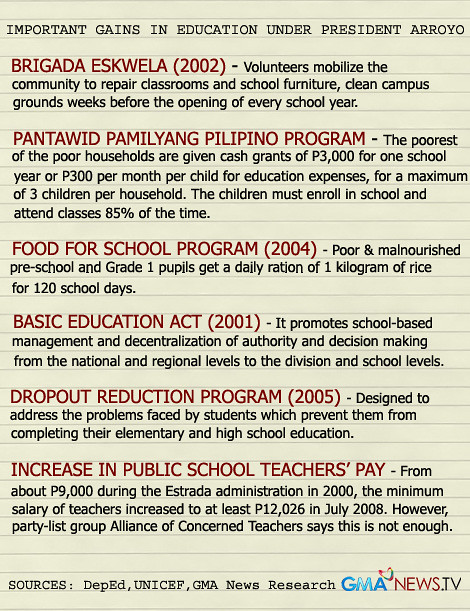

Targets met Despite the shortages, the Arroyo government can still claim achievements in the education sector.

One successful case of decongestion is the Rizal High School in Pasig City. The school used to be notorious for being the secondary school with the biggest population, with almost 16,000 students when President Arroyo came to power in 2001. In 2005, with the help of the city government, the school administration reduced its pupil-to-classroom ratio from 1:65 to 1:50. For this school year, the student population plunged to about 10,000 because some of its annexes became independent public high schools. “We are still the premier public high school in Pasig. We no longer have shortages in teachers, textbooks. What is nice here is we are enjoying all these privileges with the help of the city government. Students are given free shoes, jogging pants, bags, and books in eight subject areas," said Ruth Palomares, the school’s acting principal.

Rizal High School's notable alumni include former Senate Presidents Jovito Salonga and Neptali Gonzales. Sophia Dedace

One of the factors that may have hindered the performance of the basic education sector is that instability has plagued the DepEd, government’s biggest bureaucracy, in the last decade. President Arroyo named six DepEd secretaries and one officer-in-charge during her nine-year tenure, making continuity in policy-making nearly impossible, said Alliance of Concerned Teachers newly-elected partylist Rep. Antonio Tinio. As of September 2009, the DepEd directly operated 44,691 elementary schools and 10,066 high schools nationwide. The department was subdivided into almost 200 schools divisions and 17 regional offices across the country.

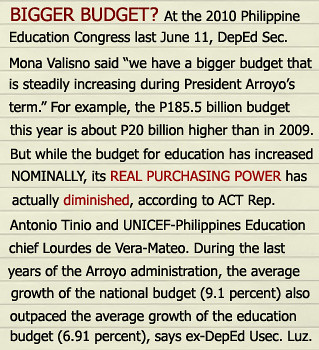

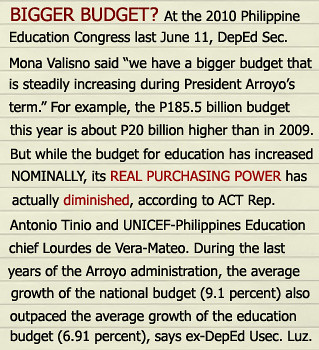

In the latest Philippine Human Development Report, former DepEd undersecretary for finance Juan Miguel Luz observed, “as with other bureaucracies, resistance to institutional change appears to be the rule in the DepEd." Worse, the DepEd has been hounded by numerous allegations of corruption and mismanagement. Citing a 2007 Commission on Audit report, the Congressional Planning and Budget Department in 2008 said the department

wasted millions in public funds. "Information and multi-media equipment packages amounting to no less than P667.95 million were neither utilized nor maximized for classroom instruction in 13 regions because they were either defective or distributed to schools which were not strictly selected in accordance with the approved criteria, resulting in the wasteful storage or utilization of the units," the CPBD said. The department has also suffered from partisan politics, one of the casualties in an administration that has been accused of weakening government institutions. Insiders at the department attest that Luz was one of their best officials during the Arroyo years. However, in 2006, Malacañang transferred him to the Department of Labor and Employment supposedly because of “political vendetta." Luz reportedly refused to clear postdated checks that President Arroyo’s social fund issued to bankroll the scholarship program of Zambales Rep. Antonio Diaz, an Arroyo ally who voted to junk the impeachment complaint against the President. As a career executive service officer, Luz questioned his transfer before the Civil Service Commission and said he could not be arbitrarily reassigned. But the CSC’s leadership, dominated by Arroyo allies, ordered Luz’ transfer to the DOLE anyway. Luz eventually resigned from government service, saying his reassignment was politically motivated. In 2008, the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism reported that Luz was among the casualties of “politics creeping into the civil service." [See:

PCIJ story on Juan Miguel Luz ]

Lost opportunities President Arroyo’s previous State of the Nation Addresses have been replete with figures of new classrooms built, new teachers hired, and new textbooks produced. But Luz said good governance is more than simply throwing money to lessen shortages. If it is serious about reform, the government needs to go beyond plugging the loopholes, he added. “The key to change in basic education is not to plug the leaks, but to build a new boat. One can deal with shortages every year, but a fast-growing population will only mean more spinning of wheels while staying in place," he said.

“In January 2001, the Arroyo administration had a nine-year window of opportunity to take a poorly-performing education system and radically restructure it. Sadly, today we have the same overcrowded structure, the same processes, and the same low education standards but with millions more children to attend to. In summary, an opportunity wasted," Luz adds. Education is the key to liberating people from poverty — that is why the 1987 Constitution says that “the state shall protect and promote the right of all citizens to quality education at all levels and shall take appropriate steps to make such education accessible to all." From his home overlooking the Payatas dumpsite, Erwin Dolera and his paper boat inspired the aspirations of so many other young people who believe that education would be vastly improved under a promising new president who was much better educated than her predecessor. Erwin, it turned out nine years later, was just one of the lucky ones. -

HS, GMANews.TV