2 of every 3 licensed guns in PHL in hands of civilians

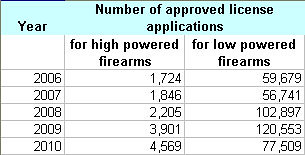

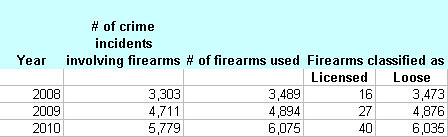

MANILA, Philippines — Gerardo Ortega, Venson Evangelista, Emerson Lozano: what do these three have in common? They were all victims of crimes involving guns. Ortega, a radio commentator in Palawan, was reportedly shot and killed by a lone gunman while he was shopping in a used-clothes store after his daily morning broadcast. Evangelista and Lozano, both of whom were used-car dealers, were both kidnapped by carjackers at gunpoint and murdered. Evangelista’s charred remains were later found in an irrigation canal in Cabanatuan City. Lozano’s body, also burned, was dumped in Porac, Pampanga. Both dealers were found with gunshot wounds in their heads. Shortly after the killings, an article posted on progun.ph, the official website of PROGUN, a local group of gun enthusiasts, urged shopkeepers, sales persons, and car dealers to keep pistols ready for protection. “Whether or not these acts were serial killings, plain robbery, or thrill kills," the author of the post argued, the incidents “now serve to highlight the need for merchants and sales persons to protect themselves." Right to life This reaction is expected. The key argument gun enthusiasts use to support their right to bear guns is the right to life. Proponents argue that, because the police are unable to protect ordinary citizens from criminal elements, they need guns to protect themselves and their families. This is particularly true in areas where armed insurgencies are still persistent. Those who don’t have guns feel vulnerable. Given the perception of rising criminality, this type of reasoning is likely to gain more adherents. Security analysts and experts, however, warn against taking this dangerous route. The easy availability of guns, according to Ateneo de Manila University professor Jennifer Santiago Oreta, tends to increase the incidence of violence against the civilian population. “Mere possession of a gun emboldens one to take drastic action," she explains. Santiago Oreta, who is with the political science department, has been studying gun proliferation in relation to private armies and has served as consultant to the Independent Commission to Investigate Private Armies, which was created by President Arroyo shortly after the infamous Maguindanao massacre. The way things are, according to Santiago Oreta, there are too many guns in circulation in the country already. In her study, “More Guns, More Risks," Santiago Oreta cites data from the Philippine National Police (PNP) showing that as of first semester of 2008, there were 1,081,074 licensed firearms in the country. Half of these (517,341) are in the National Capital Region or NCR. What is more interesting, according to her, is that only about a third (30.15%) of all legal guns in circulation are in the hands of official state actors such as the police, military, deputized government employees/ officials, elected officials, reservist, and diplomatic corps combined. Two out of every three (69.85%) legal arms currently in circulation in the Philippines are in civilian or private hands. High powered Ideally, civilians should only be allowed to own low-caliber firearms. Establishments may be allowed to arm their guards with shotguns but not military-type assault rifles such as the ones found in the Ampatuan residences, says retired Gen. Edilberto Adan, a member of the commission. The range of weapons circulating in the country is overwhelming, according to Santiago Oreta. These range from AK-47s, M-16s, M-14s, M-1s, .38 and .45 pistols, revolvers and paltik (locally-manufactured guns), to rocket propelled grenades (RPGs), M-79s, PV-49s, landmines, machine guns (30/50/60), and 81mm mortars. One particularly popular firearm in the market at the moment is the Tavor TAR-21, an Israeli-made assault rifle that sells for around P450 thousand to P800 thousand, according to Adan. Records obtained by Newsbreak from the PNP’s Firearms and Explosives Office (FEO) show that as of November 15, 2010, almost 47,000 of the 929,034 firearms licenses issued by the office covered high powered firearms. Further, while the number of approved licenses for low-powered firearms tends to fluctuate — tending to decrease during periods covered by election gun bans — the number of applications for licenses for high powered firearms has been rising steadily over the years. Table 1. Number of approved license applications  Source: Data culled by Newsbreak from records on approved firearms licenses from 2006 to 2010 by region, type, and caliber obtained from the PNP Firearms and Explosives Office. The number of licensed firearms reflected in the FEO database as of November 15, 2010 is 929,034. Not all authorized firearms in circulation in the country, however, are in this database. Those purchased and issued by the Armed Forces of the Philippines to its officers, personnel and agents are not included. Danger zone: loose firearms More worrisome than the amount of guns reflected in the FEO database are those that are not listed, FEO’s Sonia Calixto says. “If it’s licensed, you won’t use it for crime because it will be traced to you." If guns follow the required supply chain, they are theoretically traceable from the time they are manufactured or imported until each transfer of ownership. From the dealers, locally manufactured guns are brought to the PNP crime lab for ballistics. After that, they are brought to the FEO for storage and recording. The dealer only requests for the guns when they are displayed or sold. If a gun needs to be transferred to another dealer’s stockade (bodega), the dealer needs to request for a permit to transfer from the PNP FEO. Imported guns are checked for proper Customs permits and then escorted to the crime lab for ballistics testing, then to the FEO for storage. If a gun does not go through this procedure, it would be difficult for authorities to trace the firearms used in a crime to their owners. There are still gaps in the system though. The PNP crime laboratory’s database of bullet samples taken from the ballistics testing of guns during licensing is not yet fully computerized. This means that unless the actual firearm used in the crime has been recovered, there could be no way to trace it to the owner, whether the gun used is licensed, or not. Guns and crimes PNP records show that the number of crimes committed using firearms is consistently rising. In 2002, the Philippines ranked 5th globally, after South Africa, Colombia, Thailand and the United States, in terms of the number of murders committed using firearms, according to the 8th United Nations Survey on Crime Trends and the Operations of Criminal Justice Systems. Authorities say most of the guns used in committing crimes were loose firearms. Table 2. Crime indicents involving firearms

Source: Data culled by Newsbreak from records on approved firearms licenses from 2006 to 2010 by region, type, and caliber obtained from the PNP Firearms and Explosives Office. The number of licensed firearms reflected in the FEO database as of November 15, 2010 is 929,034. Not all authorized firearms in circulation in the country, however, are in this database. Those purchased and issued by the Armed Forces of the Philippines to its officers, personnel and agents are not included. Danger zone: loose firearms More worrisome than the amount of guns reflected in the FEO database are those that are not listed, FEO’s Sonia Calixto says. “If it’s licensed, you won’t use it for crime because it will be traced to you." If guns follow the required supply chain, they are theoretically traceable from the time they are manufactured or imported until each transfer of ownership. From the dealers, locally manufactured guns are brought to the PNP crime lab for ballistics. After that, they are brought to the FEO for storage and recording. The dealer only requests for the guns when they are displayed or sold. If a gun needs to be transferred to another dealer’s stockade (bodega), the dealer needs to request for a permit to transfer from the PNP FEO. Imported guns are checked for proper Customs permits and then escorted to the crime lab for ballistics testing, then to the FEO for storage. If a gun does not go through this procedure, it would be difficult for authorities to trace the firearms used in a crime to their owners. There are still gaps in the system though. The PNP crime laboratory’s database of bullet samples taken from the ballistics testing of guns during licensing is not yet fully computerized. This means that unless the actual firearm used in the crime has been recovered, there could be no way to trace it to the owner, whether the gun used is licensed, or not. Guns and crimes PNP records show that the number of crimes committed using firearms is consistently rising. In 2002, the Philippines ranked 5th globally, after South Africa, Colombia, Thailand and the United States, in terms of the number of murders committed using firearms, according to the 8th United Nations Survey on Crime Trends and the Operations of Criminal Justice Systems. Authorities say most of the guns used in committing crimes were loose firearms. Table 2. Crime indicents involving firearms  Source: Data culled by Newsbreak from records of the PNP Firearms and Explosives Office on crimes involving firearms. As of 2008, the PNP reported that there were 482,162 loose firearms in the country. The data might even be understated, according to Santiago Oreta. “There is no accurate estimate of illegal guns," she says. The PNP defines the number of loose firearms to include those that were previously licensed, hence reflected in its database, but whose licenses were not renewed after they expired. The fact that the PNP was able to release an exact number, however, implies that this data actually represents the number of guns with expired licenses, according to Santiago Oreta. Porous borders, largely unregulated by the government, allow a steady stream of smuggled firearms of all calibers and models to filter into the local market, security sector experts explain. Illicit gun manufacture also thrives in such areas as Danao, Cebu, Santiago Oreta says in her study. All these contribute to the public feeling of insecurity that drives more civilians to acquire guns, Santiago Oreta says. But it’s a vicious cycle, she warns. While the possession of a gun can make its owner feel secure, Santiago Oreta points out that its proliferation can also make people feel more insecure. It also compels the state to channel more funds for its military and police spending to combat lawlessness and violence—diverting funds from crucial services such as education, health care, infrastructure, and livelihood. In turn, such “unmet human needs" can fuel criminality and armed hostilities that, ultimately, push state actors and ordinary people further into the race to acquire more guns. --- This series on the security sector is done in partnership with the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Read the story as published in Newsbreak.ph. For updates on this story or to send feedback, email editorial@newsbreak.ph or send a response to @newsbreak_ph on Twitter. You may also post comments on Facebook.com/newsbreak.ph. —With JMA/JV, GMANews.TV

Source: Data culled by Newsbreak from records of the PNP Firearms and Explosives Office on crimes involving firearms. As of 2008, the PNP reported that there were 482,162 loose firearms in the country. The data might even be understated, according to Santiago Oreta. “There is no accurate estimate of illegal guns," she says. The PNP defines the number of loose firearms to include those that were previously licensed, hence reflected in its database, but whose licenses were not renewed after they expired. The fact that the PNP was able to release an exact number, however, implies that this data actually represents the number of guns with expired licenses, according to Santiago Oreta. Porous borders, largely unregulated by the government, allow a steady stream of smuggled firearms of all calibers and models to filter into the local market, security sector experts explain. Illicit gun manufacture also thrives in such areas as Danao, Cebu, Santiago Oreta says in her study. All these contribute to the public feeling of insecurity that drives more civilians to acquire guns, Santiago Oreta says. But it’s a vicious cycle, she warns. While the possession of a gun can make its owner feel secure, Santiago Oreta points out that its proliferation can also make people feel more insecure. It also compels the state to channel more funds for its military and police spending to combat lawlessness and violence—diverting funds from crucial services such as education, health care, infrastructure, and livelihood. In turn, such “unmet human needs" can fuel criminality and armed hostilities that, ultimately, push state actors and ordinary people further into the race to acquire more guns. --- This series on the security sector is done in partnership with the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Read the story as published in Newsbreak.ph. For updates on this story or to send feedback, email editorial@newsbreak.ph or send a response to @newsbreak_ph on Twitter. You may also post comments on Facebook.com/newsbreak.ph. —With JMA/JV, GMANews.TV