Its “uncharted maps" to “paths of self preservation where there aren’t any," make Revolutionary Routes the perfect title for Angela Stuart-Santiago’s new book. “No one’s made into a hero" in this story of an old Tayabas clan “finding community in times of revolt and revolution." Historian Reynaldo Ileto calls it an “alternative history," with family secrets revealed casting new light on written history. It began with a curious grandson asking his Lola about her life in bygone eras. Concepcion (a.k.a. Concha) Herrera vda de Umali, 88, first responded with Spanish proverbs, then succumbed to a writing fever. In a year, she filled ten notebooks with the handwritten Fragmentos de mi juventud (Fragments of My Youth). Only her Spanish-speaking daughters could read it with ease, but with her passing in 1980, they saw what a pity it would be for her English-speaking descendants to miss out on Lola’s life. Her eldest daughter Nena struggled with incipient blindness to do the translation. Blind by the time she finished, she passed on an heirloom of memory to her writer daughter Angela. “I was reading a final draft of 800 pages in one sweep for the first time... and it hit me," Angela writes. “My great great Lola Paula jailed by a friar in 1891, my great Lolo Isidro jailed by the American military government in 1901, Lolo Tomas forced into exile by pro-Quezon Forces in 1910-1912, my uncle Crisostomo ‘Mitoy’ Salcedo executed by a political rival, a fellow guerrilla during the Japanese Occupation, and finally my uncle the Congressman jailed in 1951-1958 at the height of Magsaysay’s anti-Huk campaign. Lola’s accounts of those dark times are rather bleak and dry but tell enough to indicate that not one of the five deserved punishment. Lola least of all."

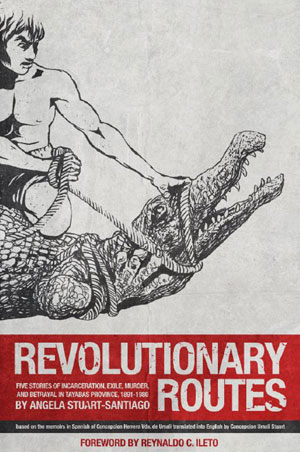

Art by Mervin Malonzo - Noli me tangere’s Elias subduing the crocodile in the garden of Isidro and Juliana Herrera’s Tiaong mansion designed by Tomas Mapua in 1928. “A message from Rizal set in stone by Lolo Isidro in the time of America some 83 years ago... He must have seen that America was...here to stay; and it would take another revolution to regain lost ground." - A.S.Santiago

There began this tell-all book set in old Tayabas, Manila, Macau and Hong Kong, spanning the last Spanish decade, Revolution, the Fil-American war, Japanese occupation and early independence. Artfully, Angela threads the narrative like a film, with quotations from

Fragmentos, letters, press clippings, court records, family lore and insights on different Philippine periods by first-rate historians. We meet the story’s first protagonist - the rice-farming peasant landowner in Tiaong, Paula Cerrada-Herrera – in the cholera epidemic of 1890. When a family of her tenants die, all were buried in paupers’ graves, but it falls to Paula to bury the youngest. Refusing to pay Tiaong’s

cura parroco “an obscene amount of money" for Catholic rites, she buried the boy outside the cemetery. For that she was arrested and taken on a 30-km march to prison in the

cabecera, “elbows tied behind her back," at age 50. Rizal was away when his own mother was marched to prison on false charges. Paula’s son Isidro was right there for her - walking incognito all over Tayabas, gathering complaints against the

cura. Then he did the unthinkable – filed a case against the

fraile in Manila. Paula was tried and released six months after her arrest; the erring friar was exiled. Isidro Herrera’s path was set. This educated son of a wealthy peasant joined the Revolution of 1896. By the summer of 1897, “he was contributing palay to the revolution and buying guns to secure his rice farms." As hostilities escalated, he moved his family from Sariaya town to a Tiaong barrio, while moving around “in service to our country." His wife Juliana maintained a place for revolutionaries far from towns where Spanish rule was ending in violence. Alas, American imperialism took over, forcing Isidro and Juliana’s return to town at a new master’s orders. They were adjusting to life in uneasy peace when past support for the revolution got Isidro unjustly arrested. A sympathetic American lawyer and Juliana’s saved-up dollars secured his release, but more troubles awaited. Things were settling down under American rule when the up-and-coming provincial fiscal Manuel Quezon came into their lives. When their

unica hija Concha was engaged to the Batangueño orator, writer, revolutionary and future lawyer, Tomas Umali, Quezon volunteered to be their wedding sponsor. Next governor of Tayabas, Don Manuel asked Tomas to make him a partner in a Tayabas railroad expropriation deal. Consent cost Tomas dearly. Corruption in the deal emerged, leading to his arrest, disbarment and exile, persuaded by his fellow-Masons to save Quezon’s name at the cost of his own. When Quezon was Commonwealth President, Concha and Tomas Umali had come to terms enough to ask him to sign appointment papers for their son-in-law, Crisostomo ‘Mitoy’ Salcedo, as local justice of the peace. World War II changed the game, plunging the clan into successive evacuations,

zona for the men and harassment from all sides, guerrillas included. Tragedy approached when Vicente Umali (no relation to Tomas), Mitoy’s old college rival jealous of his position, became both a Japanese-collaborating mayor and a general of Quezon’s guerrillas. Vicente ordered the burning of the town hall, framed Mitoy with terrorized witnesses, then ended it all by stabbing him to death. Insult to injury, he was exonerated under a new law pardoning guerrilla murders in wartime. Justice delayed, denied, and aborted also visited the life of the fifth clan protagonist in the Huk era of American-led Cold War. The efforts of the Umalis’ eldest son Narciso to win back Huks terrorizing and freezing commerce in the countryside helped him win a Tayabas congressional seat in 1949. In 1951 Huks burned the home of the Tiaong mayor, Marcial Punzalan, who called it a communist plot and accused Naning as ringleader. This canard of a landowning “communist big fish" fit nicely with the CIA’s anti-communist campaign led by Ramon Magsaysay. Tried and convicted for rebellion, murder and arson, Naning Umali spent nearly seven years in prison. Malacañang ignored the congressional majority’s appeals. The Supreme Court stood pat despite recantation by the main witness against him, followed by captured Huk documents claiming the deed. (Naning Umali was on their hit list, in fact.) Only with Magsaysay’s death did President Carlos Garcia pardon an innocent man. If alternative history disturbs you, it must be because “the past is present still." -

YA, GMA News