Filtered By: Topstories

News

Why Malacañang doesn’t serve tap water

By PATERNO ESMAQUEL II, GMA News

(Last in a 3-part series) If the government-led committee on Metro Manila water quality is to be believed, tap water from Maynilad Water Services Inc. and Manila Water Company Inc. is safe to drink. Malacañang itself, however, seems unconvinced. Its actions speak louder than words: The Office of the President doesn’t serve tap water.  Isabel Javier, Malacañang’s director for Internal House Affairs, says the Palace opts to serve bottled or filtered water in its day-to-day activities. Such has always been the case, Javier says. Two staff members of the Malacañang Socials Office, which handles Palace social functions such as state dinners and vins d’ honneur, confirm this practice. “Eh kasi hindi naman siya safe inumin, ‘di ba? (It’s unsafe to drink, isn’t it?)" explains Socials Office staff member Girlie Recinto. “Ewan ko sa iba kung uso pa ang tap water (I’m not sure if other people still drink tap water)," adds her colleague Marivic Manlapig. “Kasi ‘di ba marami nang nasira ang tiyan dahil sa maruming tubig (Isn’t it that people get stomach problems from it)?" Malacañang’s water supplier, Maynilad, regularly gets positive certifications from the Metro Manila Drinking Water Quality Monitoring Committee, a multi-sectoral body mandated to monitor the quality of tap water in Metro Manila and surrounding areas. Both Maynilad and Manila Water cite the committee’s findings to vouch for the potability of their water supplies–that is, until they reach a customer’s water meter. From this point, the two concessionaires explain, water quality becomes the customer’s responsibility.

Isabel Javier, Malacañang’s director for Internal House Affairs, says the Palace opts to serve bottled or filtered water in its day-to-day activities. Such has always been the case, Javier says. Two staff members of the Malacañang Socials Office, which handles Palace social functions such as state dinners and vins d’ honneur, confirm this practice. “Eh kasi hindi naman siya safe inumin, ‘di ba? (It’s unsafe to drink, isn’t it?)" explains Socials Office staff member Girlie Recinto. “Ewan ko sa iba kung uso pa ang tap water (I’m not sure if other people still drink tap water)," adds her colleague Marivic Manlapig. “Kasi ‘di ba marami nang nasira ang tiyan dahil sa maruming tubig (Isn’t it that people get stomach problems from it)?" Malacañang’s water supplier, Maynilad, regularly gets positive certifications from the Metro Manila Drinking Water Quality Monitoring Committee, a multi-sectoral body mandated to monitor the quality of tap water in Metro Manila and surrounding areas. Both Maynilad and Manila Water cite the committee’s findings to vouch for the potability of their water supplies–that is, until they reach a customer’s water meter. From this point, the two concessionaires explain, water quality becomes the customer’s responsibility.  Problems and health-related concerns on tap water begin at the household level, says Caloocan Rep. Mary Mitzi Cajayon, who inspected water services as part of the Congressional Oversight Committee on the Clean Water Act. Based on her own review of water treatment processes, Cajayon is certain that Maynilad and Manila Water subject their resources to proper treatment. But the solon notes, “'Yung pinagdadaanan, tapos ‘yung ibang connection ng establishment, hindi ka nakakasiguro (The water pipes and the other connections of an establishment leave us uncertain)." Restos should serve ‘clean’ water Cajayon speaks from first-hand experience. The congresswoman, who comes from a poor family, contracted typhoid fever while in elementary grade and twice suffered amoebiasis later in life. Both are water-borne diseases. Cajayon says her family used to drink tap water when she was a child. She is now advocating the public’s right to potable water, particularly in dining establishments. In the 15th Congress, Cajayon filed House Bill 2341 that seeks “to require all establishments offering dining services to serve safe drinking water." The bill requires restaurants and other eating places to serve only purified water to their customers. “In cases when purified drinking water is not available, dining establishments shall be required to serve or provide instead bottled water to their clients free of charge," says Cajayon’s proposed legislation. Her bill does not categorize tap water as “safe," explains one of Cajayon’s staff members, Amado Cosido. It defines safe drinking water as that which is “sufficiently free from biological, chemical, radiological, or physical impurities, such that individuals will not be exposed to disease or harmful physiological effects upon consumption."

Problems and health-related concerns on tap water begin at the household level, says Caloocan Rep. Mary Mitzi Cajayon, who inspected water services as part of the Congressional Oversight Committee on the Clean Water Act. Based on her own review of water treatment processes, Cajayon is certain that Maynilad and Manila Water subject their resources to proper treatment. But the solon notes, “'Yung pinagdadaanan, tapos ‘yung ibang connection ng establishment, hindi ka nakakasiguro (The water pipes and the other connections of an establishment leave us uncertain)." Restos should serve ‘clean’ water Cajayon speaks from first-hand experience. The congresswoman, who comes from a poor family, contracted typhoid fever while in elementary grade and twice suffered amoebiasis later in life. Both are water-borne diseases. Cajayon says her family used to drink tap water when she was a child. She is now advocating the public’s right to potable water, particularly in dining establishments. In the 15th Congress, Cajayon filed House Bill 2341 that seeks “to require all establishments offering dining services to serve safe drinking water." The bill requires restaurants and other eating places to serve only purified water to their customers. “In cases when purified drinking water is not available, dining establishments shall be required to serve or provide instead bottled water to their clients free of charge," says Cajayon’s proposed legislation. Her bill does not categorize tap water as “safe," explains one of Cajayon’s staff members, Amado Cosido. It defines safe drinking water as that which is “sufficiently free from biological, chemical, radiological, or physical impurities, such that individuals will not be exposed to disease or harmful physiological effects upon consumption."  The bill also mandates local government units (LGUs), assisted by the Department of Health (DOH) and the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), to check if dining establishments comply with these requirements. Cajayon notes that in the current set-up, dining establishments do not strictly comply with the Sanitation Code of the Philippines in terms of water safety. Signed by then-President Ferdinand Marcos in 1975, the Sanitation Code, or Presidential Decree No. 856, is a set of standards on public health and sanitation. Cosido says the public cannot simply “rely" on dining establishments to provide them with safe drinking water, thus the need for the supplemental clean water bill. The proposed law will require violators to pay a fine of P10,000 to P50,000, with the possibility of having their business permits and licenses revoked. Responsible parties after the meter But a health department official says such a bill is unnecessary. “Kaya nga nire-regulate mo ‘yung mga service providers… para sabihin mong talagang ang pino-provide nila is quality water (But that is why we regulate service providers…to assure the public that they provide them with quality water)," says Engr. Joselito Riego de Dios, chief health program officer of the DOH Environmental and Occupational Health Office.

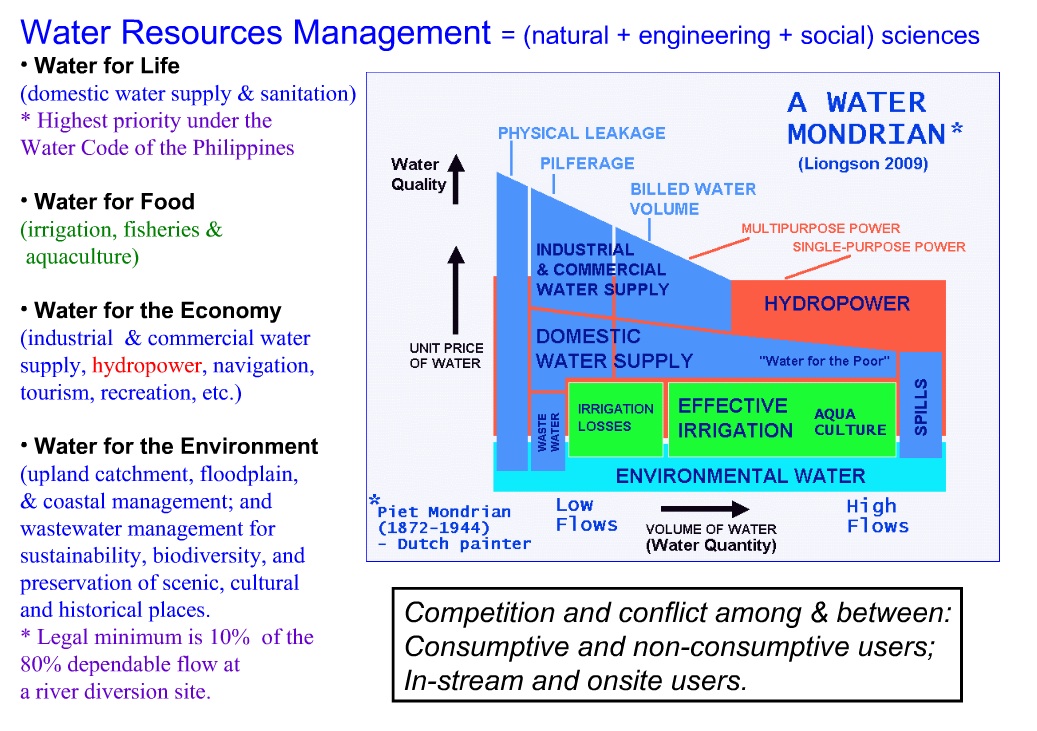

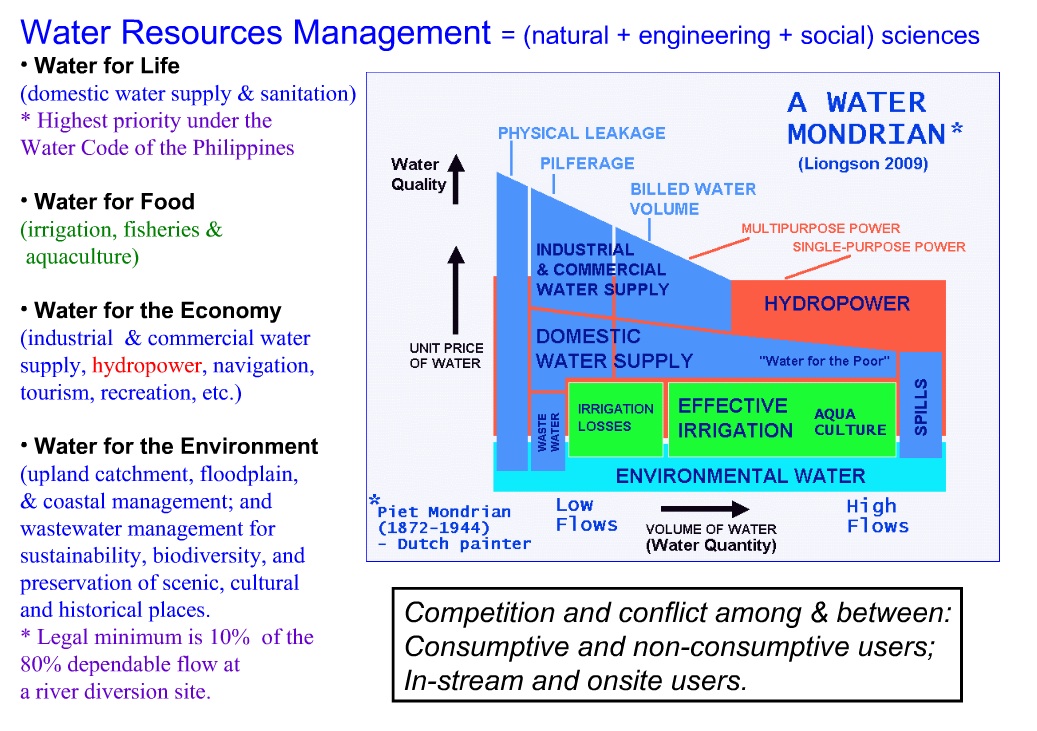

The bill also mandates local government units (LGUs), assisted by the Department of Health (DOH) and the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), to check if dining establishments comply with these requirements. Cajayon notes that in the current set-up, dining establishments do not strictly comply with the Sanitation Code of the Philippines in terms of water safety. Signed by then-President Ferdinand Marcos in 1975, the Sanitation Code, or Presidential Decree No. 856, is a set of standards on public health and sanitation. Cosido says the public cannot simply “rely" on dining establishments to provide them with safe drinking water, thus the need for the supplemental clean water bill. The proposed law will require violators to pay a fine of P10,000 to P50,000, with the possibility of having their business permits and licenses revoked. Responsible parties after the meter But a health department official says such a bill is unnecessary. “Kaya nga nire-regulate mo ‘yung mga service providers… para sabihin mong talagang ang pino-provide nila is quality water (But that is why we regulate service providers…to assure the public that they provide them with quality water)," says Engr. Joselito Riego de Dios, chief health program officer of the DOH Environmental and Occupational Health Office.  Riego de Dios also points out that at least two other laws protect water after the meter from possible contamination. These are the National Building Code of the Philippines, or Republic Act (RA 6541), and the Plumbing Law, or RA 1378. Both commercial and residential establishments are covered by the Building Code and the Plumbing Law, adds Riego de Dios. The Building Code, signed by then-President Ferdinand Marcos in 1972, sets minimum standards and requirements for buildings and other structures “to safeguard life, health, property, and public welfare." The Plumbing Law, signed by then-President Ramon Magsaysay in 1955, regulates the practice of plumbing by setting basic principles for the trade. Plumbing facilities in all buildings for human habitation should conform with the Plumbing Law, according to the Building Code. Plumbing systems include pipes and drainage systems that could cause water contamination. Thus, to acquire a permit, any building “has to be designed or constructed under the supervision of a licensed engineer," says Riego de Dios. “Kaya nga pati ‘yung plano, may plumbing plans (That’s why the building plan should also include plumbing plans)," he adds. Building officials of LGUs are tasked to implement both the Building Code and the Plumbing Law, according to Riego de Dios. For commercial establishments such as restaurants, he says the Sanitation Code also comes into play. “So dapat ‘yung local health office, as part nung regulating the business, tinitingnan din nila ‘yung tubig na isine-serve nu’ng restaurant," he said. Government’s limitations However, this is easier said than done. “Hindi mo masasabing hundred percent of the local government units, namo-monitor ‘yung mga operations ng establishments (We cannot say 100 percent of the local government units get to monitor the operations of establishments)," says Riego de Dios. In particular, he cites the difficulties in implementing the Sanitation Code provisions on commercial establishments. “May limitation sa tao, sa number ng sanitary inspectors. Eh sa dami ng establishment, hindi mo mamo-monitor lahat ‘yun (There is a limitation in terms of personnel, of the number of sanitary inspectors. With the sheer number of establishments, you cannot easily monitor them)," he says. He also attributes the problem to a lack of funds and other administrative concerns. “May limitation in terms of water quality testing. May limitation sa availability ng water laboratories, ‘yung mga gano’n (There are limitations in terms of water quality testing. There are also limitations in the availability of water laboratories, things like that)," he adds. Bureaucratic quagmire The issue of potable water transcends individual consumers, water suppliers like Maynilad and Manila Water, regulatory bodies, and local government units. “Malawak ang water eh (Water is a wide subject)," says Engr. Leonardo Liongson, professor at the University of the Philippines Institute of Civil Engineering. Liongson, who also holds a doctorate in water resource administration and hydrology, explains water potability in the context of the other uses of water. In a diagram (see below), he illustrates how domestic water supply and sanitation (“water for life"), which are used for drinking, interacts with water meant for other functions (“water for food," “water for the economy," and “water for the environment"). (See diagram below)

Riego de Dios also points out that at least two other laws protect water after the meter from possible contamination. These are the National Building Code of the Philippines, or Republic Act (RA 6541), and the Plumbing Law, or RA 1378. Both commercial and residential establishments are covered by the Building Code and the Plumbing Law, adds Riego de Dios. The Building Code, signed by then-President Ferdinand Marcos in 1972, sets minimum standards and requirements for buildings and other structures “to safeguard life, health, property, and public welfare." The Plumbing Law, signed by then-President Ramon Magsaysay in 1955, regulates the practice of plumbing by setting basic principles for the trade. Plumbing facilities in all buildings for human habitation should conform with the Plumbing Law, according to the Building Code. Plumbing systems include pipes and drainage systems that could cause water contamination. Thus, to acquire a permit, any building “has to be designed or constructed under the supervision of a licensed engineer," says Riego de Dios. “Kaya nga pati ‘yung plano, may plumbing plans (That’s why the building plan should also include plumbing plans)," he adds. Building officials of LGUs are tasked to implement both the Building Code and the Plumbing Law, according to Riego de Dios. For commercial establishments such as restaurants, he says the Sanitation Code also comes into play. “So dapat ‘yung local health office, as part nung regulating the business, tinitingnan din nila ‘yung tubig na isine-serve nu’ng restaurant," he said. Government’s limitations However, this is easier said than done. “Hindi mo masasabing hundred percent of the local government units, namo-monitor ‘yung mga operations ng establishments (We cannot say 100 percent of the local government units get to monitor the operations of establishments)," says Riego de Dios. In particular, he cites the difficulties in implementing the Sanitation Code provisions on commercial establishments. “May limitation sa tao, sa number ng sanitary inspectors. Eh sa dami ng establishment, hindi mo mamo-monitor lahat ‘yun (There is a limitation in terms of personnel, of the number of sanitary inspectors. With the sheer number of establishments, you cannot easily monitor them)," he says. He also attributes the problem to a lack of funds and other administrative concerns. “May limitation in terms of water quality testing. May limitation sa availability ng water laboratories, ‘yung mga gano’n (There are limitations in terms of water quality testing. There are also limitations in the availability of water laboratories, things like that)," he adds. Bureaucratic quagmire The issue of potable water transcends individual consumers, water suppliers like Maynilad and Manila Water, regulatory bodies, and local government units. “Malawak ang water eh (Water is a wide subject)," says Engr. Leonardo Liongson, professor at the University of the Philippines Institute of Civil Engineering. Liongson, who also holds a doctorate in water resource administration and hydrology, explains water potability in the context of the other uses of water. In a diagram (see below), he illustrates how domestic water supply and sanitation (“water for life"), which are used for drinking, interacts with water meant for other functions (“water for food," “water for the economy," and “water for the environment"). (See diagram below)

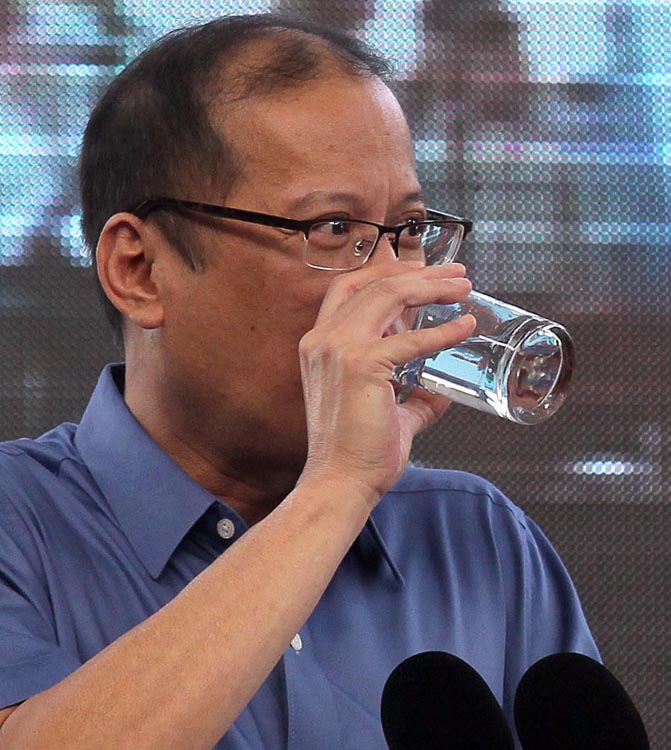

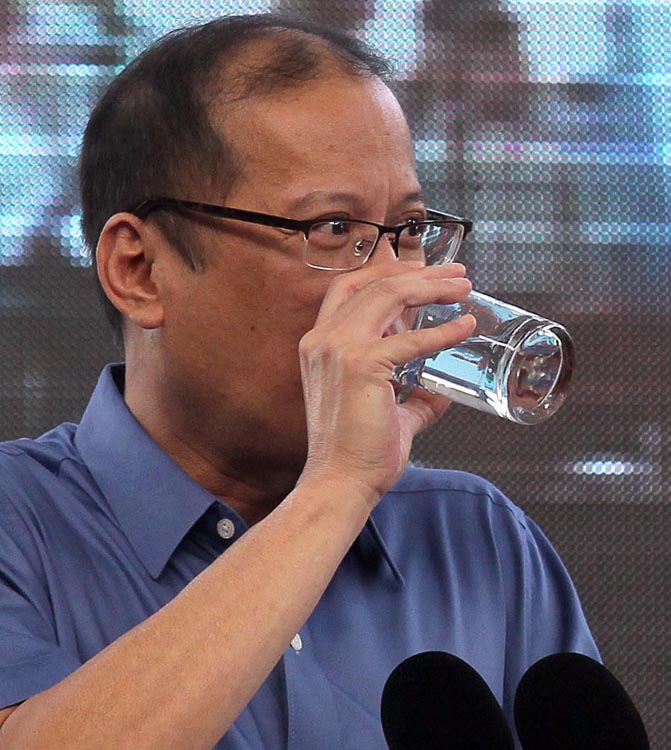

Dealing with a coughing fit, the President drinks water during his speech at a World Water Day event last March. Gil Nartea/Malacañang Photo

A government-led committee certifies water as safe until a household’s water meter – from where a customer is responsible for keeping water safe. Hub Pacheco

Restaurants need to serve “safe" drinking water to their customers, says Caloocan City Rep. Mary Mitzi Cajayon. Hub Pacheco

Water is not only used for drinking but also for cooking. How sure are we that the water in our food is safe? Hub Pacheco

Diagram courtesy of Engr. Leonardo Liongson, UP Institute of Civil Engineering

Tips for keeping water safe

Pinky Tobiano, a chemist and founder of the independent water laboratory Qualibet Testing Services Corp., says the public can do its share of keeping the water safe through the following: 1. Use homemade water filters. To remove sediments and other physical impurities, households can make a do-it-at-home filter from socks or stockings wrapped around a water spout. Putting some charcoal inside the stockings also helps. “The charcoal absorbs the excess ammonia and smell that goes into the water," Tobiano explains. 2. Disinfect cisterns. Households with water cisterns should clean their tanks at least once every three months. An effective way to do this is to flush out the bacteria using a solution with one part Clorox, or any safe disinfectant, for every 1,000 liters of water. “Water tanks are dark. Moist, dark, humid places are the best for bacteria, fungi, yeasts, and molds," she says. 3. Maintain water dispensers properly. These should be cleaned at least once a month. “Nagkaka-mold na minsan, kaya ‘pag chineck nila, ‘Bakit ganyan?’ Ayun pala, when we open the dispenser, ‘Ay, hindi naman nililinisan sa loob’," Tobiano says. —Paterno Esmaquel II, GMA News

More Videos

Most Popular