ADVERTISEMENT

Filtered by: Topstories

News

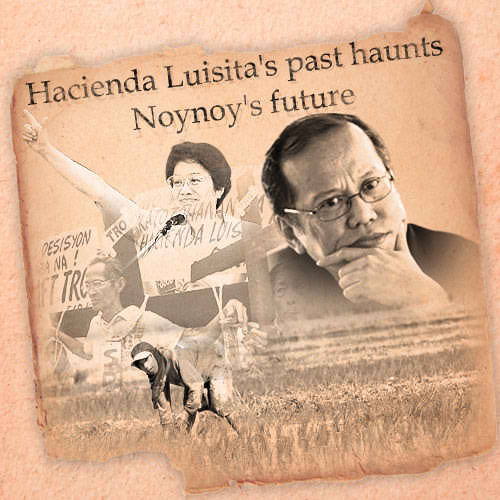

Hacienda Luisita's past haunts Noynoy's future

By STEPHANIE DYCHIU

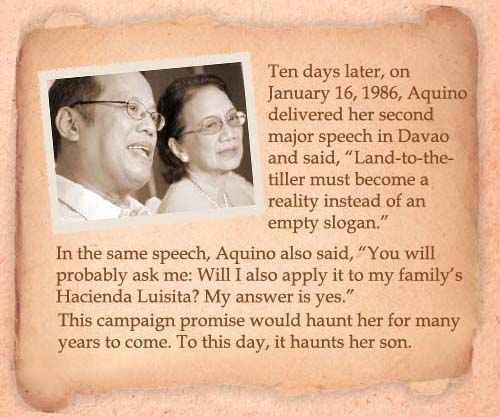

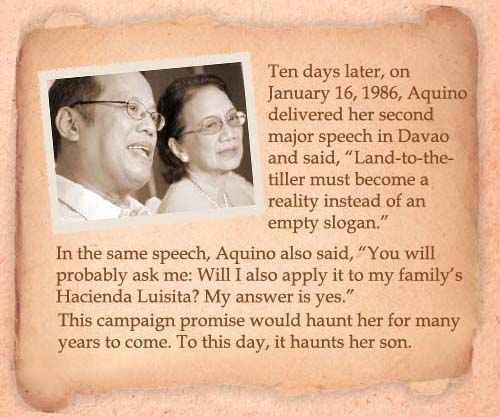

This week the country commemorates the tragic shooting of protesting farmers on January 22, 1987, an incident better known as the Mendiola massacre. Along with the Hacienda Luisita massacre of November 16, 2004, these two incidents represent the darker side of the Aquino legacy. The struggle between farmers and landowners of Hacienda Luisita is now being seen as the first real test of character of presidential candidate Noynoy Cojuangco Aquino, whose family has owned the land since 1958. Our research shows that the problem began when government lenders obliged the Cojuangcos to distribute the land to small farmers by1967, a deadline that came and went. Pressure for land reform on Luisita since then reached a bloody head in 2004 when seven protesters were killed near the gate of the sugar mill in what is now known as the Luisita massacre. This is the story of the hacienda and its farmers, an issue that is likely to haunt Aquino as he travels the campaign trail for the May 2010 elections. Below is part one. Part two is here, part three here and part four here. First of a series Senator Noynoy Cojuangco Aquino has said he only owns 1% of Hacienda Luisita. Why is he being dragged into the hacienda’s issues? This is one of the most common questions asked in the 2010 elections. To find the answer, GMANews.TV traveled to Tarlac and spoke to Luisita’s farm workers and union leaders. A separate interview and review of court documents was then conducted with the lawyers representing the workers’ union in court. GMANews.TV also examined the Cojuangcos’ court defense and past media and legislative records on the Luisita issue. The investigation yielded illuminating insights into Senator Noynoy Aquino’s involvement in Hacienda Luisita that have not been openly discussed since his presidential bid. Details are gradually explored in this series of special reports. A background on the troubled history of Hacienda Luisita is essential to understanding why the issue is forever haunting Senator Noynoy Aquino and his family.

(Click here to view the the Cojuangco family tree) Government loans given to Cojuangco Jose Cojuangco, Sr. received significant preferential treatment and assistance from the government to facilitate his takeover of Hacienda Luisita and Central Azucarera de Tarlac in 1957. To acquire a controlling interest in Central Azucarera de Tarlac, Cojuangco had to pay the Spaniards in dollars. He turned to the Manufacturer’s Trust Company in New York for a 10-year, $2.1 million loan. Dollars were tightly regulated in those times. To ease the flow of foreign exchange for Cojuangco’s loan, the Central Bank of the Philippines deposited part of the country’s international reserves with the Manufacturer’s Trust Company in New York. LAND REFORM AND SOCIAL JUSTICE

The Central Bank did this on the condition that Cojuangco would simultaneously purchase the 6,443-hectare Hacienda Luisita, “with a view to distributing this hacienda to small farmers in line with the Administration’s social justice program." (Central Bank Monetary Board Resolution No. 1240, August 27, 1957). To finance the purchase of Hacienda Luisita, Cojuangco turned to the GSIS (Government Service Insurance System). His application for a P7 million loan said that 4,000 hectares of the hacienda would be made available to bonafide sugar planters, while the balance 2,453 hectares would be distributed to barrio residents who will pay for them on installment. The GSIS approved a P5.9 million loan, on the condition that Hacienda Luisita would be “subdivided among the tenants who shall pay the cost thereof under reasonable terms and conditions". (GSIS Resolution No. 1085, May 7, 1957; GSIS Resolution No. 3202, November 25, 1957) Later, Jose Cojuangco, Sr. requested that the phrase be amended to “. . . shall be sold at cost to tenants, should there be any" (GSIS Resolution No. 356, February 5, 1958). This phrase would be cited later on as justification not to distribute the hacienda’s land. On April 8, 1958, Jose Cojuangco, Sr.’s company, the Tarlac Development Corporation (TADECO), became the new owner of Hacienda Luisita and Central Azucarera de Tarlac. Ninoy Aquino was appointed the hacienda’s first administrator.

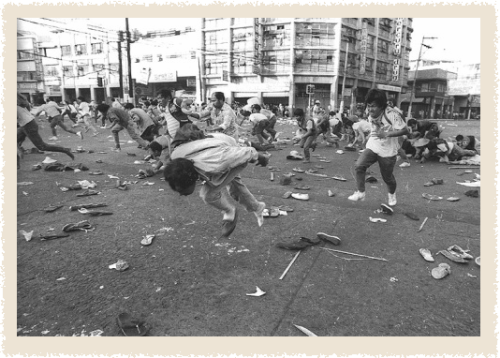

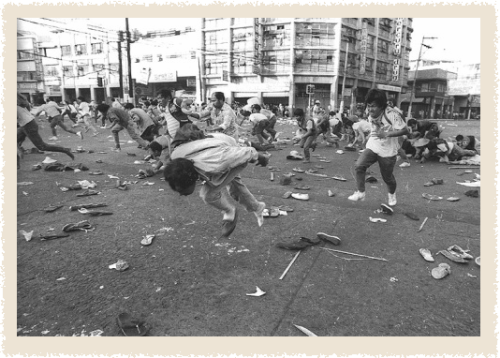

In a protest march for land reform in January 1987, 13 protesters were killed near Malacañang in what has gone down in history as the Mendiola Massacre, a low point in the administration of former President Corazon C. Aquino. Photo by Mon Acasio Under pressure after the bloodshed in Mendiola, Aquino fast-tracked the passage of the land reform law. The new 1987 Constitution took effect on February 11, 1987, and on July 22, 1987, Aquino issued Presidential Proclamation 131 and Executive Order No. 229 outlining her land reform program. She expanded its coverage to include sugar and coconut lands. Her outline also included a provision for the Stock Distribution Option (SDO), a mode of complying with the land reform law that did not require actual transfer of land to the tiller. (Aquino’s July 22, 1987 “midnight decree", as Juan Ponce Enrile called it back then, raised eyebrows because it was issued just days before the legislative powers Aquino took in 1986 were going to revert back to Congress on July 28, 1987, the first regular session of the new Congress after the May 1987 elections. The timing insured the passage of the SDO.) LAND REFORM AND SDO

Cory withdraws case vs. Cojuangcos On May 18, 1988, the Court of Appeals dismissed the case filed in 1980 by the Philippine government—under Marcos—against the Cojuangco company TADECO to compel the handover of Hacienda Luisita. It was the Philippine government itself—under Aquino—that filed the motion to dismiss its own case against TADECO, saying the lands of Hacienda Luisita were going to be distributed anyway through the new agrarian reform law. The Department of Agrarian Reform and the GSIS, now headed by Aquino appointees Philip Juico and Feliciano “Sonny" Belmonte respectively, posed no objection to the motion to dismiss the case. The motion to dismiss was filed by Solicitor General Frank Chavez, also an Aquino appointee. The Central Bank, headed by Marcos appointee Jose B. Fernandez, said it would have no objection if, as determined by the Department of Agrarian Reform, the distribution of Hacienda Luisita to small farmers would be achieved under the comprehensive agrarian reform program. Stage is set for “SDO" A month after the case was dismissed, on June 10, 1988, Aquino signed the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law. Soon after, Hacienda Luisita was put under the Stock Distribution Option (SDO) that Aquino included in the law. Through the SDO, landlords could comply with the land reform law without giving land to farmers. On June 8, 1989, Juan Ponce Enrile, now Minority Floor Leader at the Senate, delivered a privilege speech questioning Aquino’s insertion of the SDO in her outline for the land reform law, and the power she gave herself through Executive Order No. 229 to preside over the Presidential Agrarian Reform Council (PARC), the body that would approve stock distribution programs, including the one for Hacienda Luisita. Enrile also questioned the Aquino administration’s withdrawal of the government’s case compelling land distribution of Hacienda Luisita to farmers. All these, Enrile said, were indications that the Cojuangcos had taken advantage of the powers of the presidency to circumvent land reform and stay in control of Hacienda Luisita. Aquino’s sidestepping of land reform would stoke the embers of conflict in Luisita, climaxing in the November 16, 2004 massacre of workers fifteen years later. TO BE CONTINUED

Part 2: Cory’s land reform legacy to test Noynoy’s political will There is a haunting resemblance between Senator Aquino’s “Hindi Ka Nag-Iisa" music video and a real-life torchlit march of Hacienda Luisita’s workers days before the November 16, 2004 massacre. What could be worth all the blood that has been spilled? The answer lies in a contentious 30-year stock distribution scheme, a legacy from former President Aquino.

Part 2: Cory’s land reform legacy to test Noynoy’s political will There is a haunting resemblance between Senator Aquino’s “Hindi Ka Nag-Iisa" music video and a real-life torchlit march of Hacienda Luisita’s workers days before the November 16, 2004 massacre. What could be worth all the blood that has been spilled? The answer lies in a contentious 30-year stock distribution scheme, a legacy from former President Aquino.

Part 3: How a worker's strike became the Luisita massacre As Sen. Noynoy Aquino campaigns for the presidency, new attention has been focused on events of five years ago when labor strife on his family's sugar estate left seven dead. This is the third of a series that examines the tortured history of Hacienda Luisita, an issue that would face another Aquino administration.

Part 3: How a worker's strike became the Luisita massacre As Sen. Noynoy Aquino campaigns for the presidency, new attention has been focused on events of five years ago when labor strife on his family's sugar estate left seven dead. This is the third of a series that examines the tortured history of Hacienda Luisita, an issue that would face another Aquino administration.  Part 4: After Luisita massacre, more killings linked to protest After the massacre of 2004, eight more people who were either leaders or supporters of the Luisita strike were murdered in Tarlac. A GMANews.TV investigation reveals that a survivor of one shooting testified in 2005 that Sen. Noynoy Aquino had appealed to him about a "superhighway", which turned out to be the now controversial SCTex.

Part 4: After Luisita massacre, more killings linked to protest After the massacre of 2004, eight more people who were either leaders or supporters of the Luisita strike were murdered in Tarlac. A GMANews.TV investigation reveals that a survivor of one shooting testified in 2005 that Sen. Noynoy Aquino had appealed to him about a "superhighway", which turned out to be the now controversial SCTex.  Part 5: Win or lose, Noynoy has to face Luisita deadlock Since 2006, Hacienda Luisita and its farmer-beneficiaries have been locked in a stalemate after the Supreme Court temporarily stopped the implementation of a government order revoking the stock distribution option of the hacienda. In the fifth and last part of this series, presidential candidate Noynoy Aquino speaks on the range of Luisita-related issues that could hound his administraiton if he wins.

Part 5: Win or lose, Noynoy has to face Luisita deadlock Since 2006, Hacienda Luisita and its farmer-beneficiaries have been locked in a stalemate after the Supreme Court temporarily stopped the implementation of a government order revoking the stock distribution option of the hacienda. In the fifth and last part of this series, presidential candidate Noynoy Aquino speaks on the range of Luisita-related issues that could hound his administraiton if he wins.

This story was first published in November 2009, the fifth anniversary of the Luisita massacre. This updated version has been expanded to accommodate additional information. Succeeding parts of this series will be published in the coming days. Part Two is here.

When Spain colonized the Philippines by force beginning 1521, its lands were claimed by the conquistadors in the name of Spain. The natives who were already there tilling the land were put under Spanish landlords, who were given royal grants to “own" the land and exact forced labor and taxes from the natives. After the Spaniards left, the Americans took over. When the Philippines became independent in 1946, history had to be set right by giving the lands back to the people whose ancestors have been tilling them for centuries. However, a new feudal system developed among the Filipinos themselves, and once again drove a wedge between the tillers and their land.

Why is land reform a big issue in the Philippines? Land reform is linked to social justice. When Spain colonized the Philippines by force beginning 1521, its lands were claimed by the conquistadors in the name of Spain. The natives who were already there tilling the land were put under Spanish landlords, who were given royal grants to “own" the land and exact forced labor and taxes from the natives. After the Spaniards left, the Americans took over. When the Philippines became independent in 1946, history had to be set right by giving the lands back to the people whose ancestors have been tilling them for centuries. However, a new feudal system developed among the Filipinos themselves, and once again drove a wedge between the tillers and their land. What is the SDO (Stock Distribution Option)? The Stock Distribution Option (SDO) was a clause in the 1988 Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) that allowed landowners to give farmers shares of stock in a corporation instead of land. The landlords then arranged to own majority share in the corporations, to stay in control. This went against the spirit of land reform, which is to give “land to the tiller". The SDO was abolished in the updated land reform law CARPER (CARP with Extensions and Revisions) that was passed in August 2009.

This story was first published in November 2009, the fifth anniversary of the Luisita massacre. This updated version has been expanded to accommodate additional information. Succeeding parts of this series will be published in the coming days. Part Two is here.

Tags: haciendaluisita

More Videos

Most Popular