Filtered by: Topstories

News

Cory’s land reform legacy to test Noynoy’s political will

By STEPHANIE DYCHIU

This week the country commemorates the tragic shooting of protesting farmers on January 22, 1987, an incident better known as the Mendiola massacre. Along with the Hacienda Luisita massacre of November 16, 2004, these two incidents represent the darker side of the Aquino legacy. The struggle between farmers and landowners of Hacienda Luisita is now being seen as the first real test of character of presidential candidate Noynoy Cojuangco Aquino, whose family has owned the land since 1958. Our research shows that the problem began when government lenders obliged the Cojuangcos to distribute the land to small farmers by1967, a deadline that came and went. Pressure for land reform on Luisita since then reached a bloody head in 2004 when seven protesters were killed near the gate of the sugar mill in what is now known as the Luisita massacre. This is the story of the hacienda and its farmers, an issue that is likely to haunt Aquino as he travels the campaign trail for the May 2010 elections. Part one is here,part three is here and part four is here. Second of a series “Hindi ka nag-iisa (You are not alone)," sing the ghosts of Luisita to Senator Noynoy Aquino. They won’t even leave his music video alone. Noynoy Aquino's Campaign Music Video (2009) A little-known fact about the Hacienda Luisita controversy is the haunting resemblance of Senator Aquino’s “Hindi Ka Nag-Iisa" music video to a real-life, torch-lit march of Luisita’s workers amid the sugarcane fields at night days before the November 16, 2004 massacre. Sa Ngalan ng Tubo documentary about Hacienda Luisita (video recorded November 2004) (Torch scenes from 1:17 - 1:29)

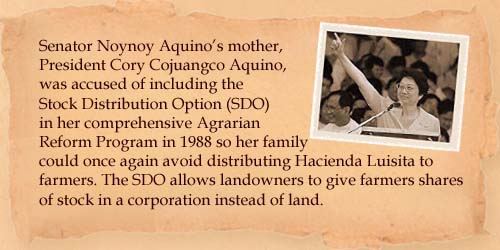

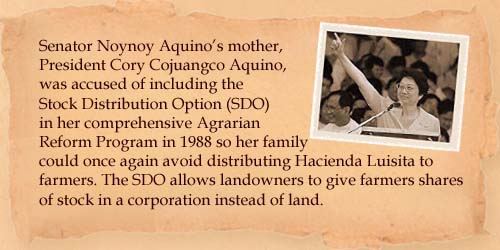

Senator Noynoy Aquino’s mother, President Cory Cojuangco Aquino, was accused of including the SDO in her outline for CARP (Presidential Proclamation 131 and Executive Order No. 229, July 22, 1987) so her family could once again avoid distributing Hacienda Luisita to farmers.

Senator Noynoy Aquino’s mother, President Cory Cojuangco Aquino, was accused of including the SDO in her outline for CARP (Presidential Proclamation 131 and Executive Order No. 229, July 22, 1987) so her family could once again avoid distributing Hacienda Luisita to farmers.

Part 1: Hacienda Luisita's past haunts Noynoy's future See Part One for the history of the farmers’ claim in Hacienda Luisita.

Part 1: Hacienda Luisita's past haunts Noynoy's future See Part One for the history of the farmers’ claim in Hacienda Luisita.

(The SDO was a clause in CARP that allowed landowners to give farmers shares of stock in a corporation instead of land. It was abolished in the updated land reform law CARPER, or CARP with Extensions and Revisions, that was passed in August 2009.)LAND ASSETS UNDERVALUED

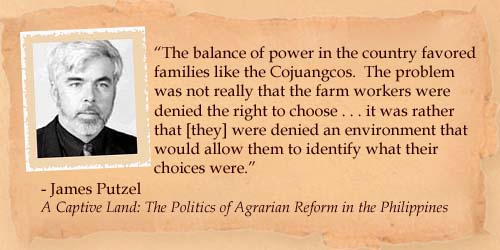

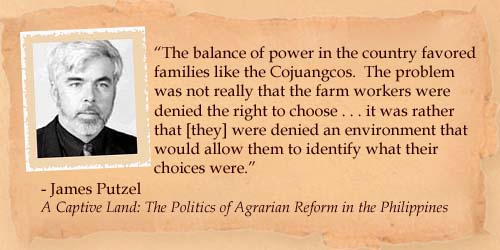

The SDO gravely damaged the potential of land reform to deliver social justice to scores of rural poor, whose votes had ironically been courted by President Aquino in 1986 by promising land reform. Aquino’s abrogation left such a deep scar that even the New York Times, in its announcement of her passing on August 1, 2009, did not let it slip: “Born into one of the country’s wealthy land-owning families, the Cojuangcos of Tarlac, Mrs. Aquino did not lead the social revolution that some had hoped for. She failed to institute effective land reform or to address the country’s fundamental structural ailment, the oligarchic control of power and politics." Cojuangcos give stocks instead of land In 1989, the Cojuangcos justified Luisita’s SDO by saying it was impractical to divide the hacienda’s 4,915.75 hectares of land among 6,296 farm workers, as this would result in less than one hectare each (0.78). A study by the private group Center for Research & Communication (now University of Asia & the Pacific) was cited to support this claim. The claim was contradicted by a study of the National Economic Development Authority (NEDA), which stated that the farm workers could still earn more with 0.78 hectares of land each than stocks. But the NEDA study was ignored by the Presidential Agrarian Reform Council (PARC), according to Eduardo Tadem, a member of the technical working group of PARC who spoke out in an October 20, 1989 report of the Philippine Daily Inquirer. The PARC was chaired by President Cory Aquino. In 2005, after its investigation into the Luisita massacre, the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) also debunked the claim that economies of scale justified Luisita’s SDO. The DAR said the issue of economies of scale could have been addressed under Section 29 of CARP, which states that workers’ cooperatives should be created in cases where dividing land was not feasible. In the column of Domini Torrevillas in the Philippine Star last Jan. 19, however, Noynoy declared: “Neither I nor the farmers are satisfied with the government’s land reform program. We have seen in Hacienda Luisita that this does not work. Luisita, which was then called Tabacalera Land, used to be 12,000 hectares. The company voluntarily gave half or 6,000 hectares for the Land Tenure Act. That is why Luisita today is only an approximate 5,500 hectares. However, the people who were provided land ended up losing or selling their property. Most of them returned to their lives as Luisita workers. “This shows that mere land distribution is not beneficial to farmers. We cannot just transfer land to a farmer and say, ‘I am done with you.’ We need to teach him until he becomes a manager, becomes the agriculture business planner, the cooperative member. We must help him find means to buy biological pest control, natural fertilizers, pesticides and farm implements."  Farmers asked to vote on SDO On May 9, 1989, Luisita’s farm workers were asked to choose between stocks or land in a referendum. The SDO won 92.9% of the vote. A second referendum and information campaign were held on October 14, 1989, and again the SDO won, this time by a 96.75% vote. In his 1992 book A Captive Land: The Politics of Agrarian Reform in the Philippines, London-based development studies expert James Putzel expressed doubt that the farmers understood the choice that was presented to them. “The outcome of the vote was entirely predictable," he wrote. “The balance of power in the country favored families like the Cojuangcos. The problem was not really that the farm workers were denied the right to choose . . . it was rather that [they] were denied an environment that would allow them to identify what their choices were." (Dr. James Putzel did extensive research on agrarian reform in the Philippines between the late 1980s to the early 1990s. He is currently a Professor of Development Studies at the London School of Economics.)

Farmers asked to vote on SDO On May 9, 1989, Luisita’s farm workers were asked to choose between stocks or land in a referendum. The SDO won 92.9% of the vote. A second referendum and information campaign were held on October 14, 1989, and again the SDO won, this time by a 96.75% vote. In his 1992 book A Captive Land: The Politics of Agrarian Reform in the Philippines, London-based development studies expert James Putzel expressed doubt that the farmers understood the choice that was presented to them. “The outcome of the vote was entirely predictable," he wrote. “The balance of power in the country favored families like the Cojuangcos. The problem was not really that the farm workers were denied the right to choose . . . it was rather that [they] were denied an environment that would allow them to identify what their choices were." (Dr. James Putzel did extensive research on agrarian reform in the Philippines between the late 1980s to the early 1990s. He is currently a Professor of Development Studies at the London School of Economics.)

This bred suspicion that the SDO was considered a done deal early on, and the two rounds of voting with the farmers were only organized to give an appearance of transparency. Aquino appointees in charge of DAR Adding to the cloud of doubt was President Aquino’s perceived influence over the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) because she had the power to appoint the department’s head. The Agrarian Reform Secretary who oversaw the farmers’ vote in Luisita in May 1989 was Philip Juico, the husband of Margie Juico, a close friend of President Aquino who also served as her Appointments Secretary. In July 1989, Aquino replaced Phillip Juico with “graft buster" Miriam Defensor-Santiago after Juico’s name was dragged into the Garchitorena land scam.

This bred suspicion that the SDO was considered a done deal early on, and the two rounds of voting with the farmers were only organized to give an appearance of transparency. Aquino appointees in charge of DAR Adding to the cloud of doubt was President Aquino’s perceived influence over the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) because she had the power to appoint the department’s head. The Agrarian Reform Secretary who oversaw the farmers’ vote in Luisita in May 1989 was Philip Juico, the husband of Margie Juico, a close friend of President Aquino who also served as her Appointments Secretary. In July 1989, Aquino replaced Phillip Juico with “graft buster" Miriam Defensor-Santiago after Juico’s name was dragged into the Garchitorena land scam.

The Garchitorena land scam The implementation of CARP during the term of President Cory Aquino was rocked by a number of scandals, one of them the Garchitorena land scam. See how the land scam was linked to President Aquino.

The Garchitorena land scam The implementation of CARP during the term of President Cory Aquino was rocked by a number of scandals, one of them the Garchitorena land scam. See how the land scam was linked to President Aquino.

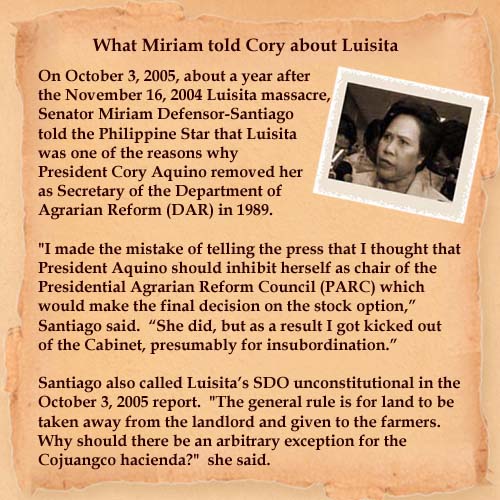

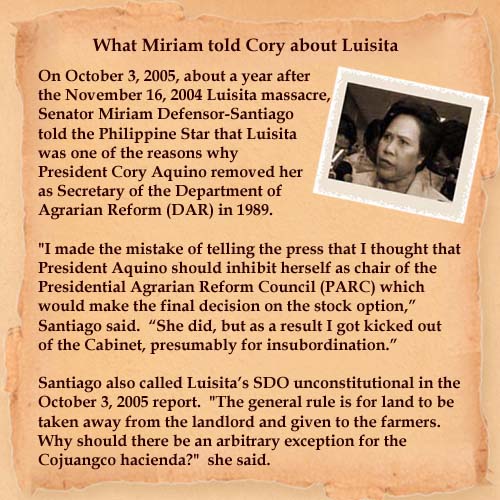

Very early into her role, Santiago, a former judge, told the media that there were “serious flaws in the law against which I am powerless" (Philippine Daily Inquirer, July 21, 1989). Santiago ended up giving Luisita’s SDO the go-signal in November 1989. Two months later, Aquino replaced Santiago. Many years later, Santiago said Aquino removed her because of something she said about Luisita.

How the Cojuangcos got majority control of Hacienda Luisita When the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program was implemented in Luisita in 1989, the farm workers’ ownership of the hacienda was pegged at 33%, while 67% was retained by the Cojuangcos. See how the Cojuangcos were able to gain control of the corporation.

How the Cojuangcos got majority control of Hacienda Luisita When the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program was implemented in Luisita in 1989, the farm workers’ ownership of the hacienda was pegged at 33%, while 67% was retained by the Cojuangcos. See how the Cojuangcos were able to gain control of the corporation.

Luisita’s SDO agreement spelled out a 30-year schedule for transferring stock to the farm workers: “At the end of each fiscal year, for a period of 30 years, the SECOND PARTY (HLI) shall arrange with the FIRST PARTY (TADECO) the acquisition and distribution to the THIRD PARTY (farm workers) on the basis of number of days worked and at no cost to them of one-thirtieth (1/30) of 118,391,976.85 shares of the capital stock of the SECOND PARTY (HLI) that are presently owned and held by the FIRST PARTY (TADECO), until such time as the entire block of 118,391,976.85 shares shall have been completely acquired and distributed to the THIRD PARTY (farm workers)." The impact of this provision was far-reaching.

NOYNOY DEFENDS COJUANGCOS

Stock distribution suddenly accelerated After the November 2004 massacre and subsequent investigation by the DAR, HLI announced on June 9, 2005 that it had given out all undistributed stocks “in one supreme act of good faith," about 15 years ahead of the 30-year schedule. It is believed this was done because the 30-year distribution period was a loophole. Way back in 1995, Dr. Jeffrey M. Riedinger, currently Dean of International Studies at Michigan State University, already said the 30-year distribution period seemed “without basis in the law" in his book Agrarian Reform in the Philippines: Democratic Transitions and Redistributive Reform. (Section 11 of DAR Administrative Order No. 10, Series of 1988 states that stocks should be transferred to beneficiaries within 60 days after the SDO is implemented. HLI had not yet been issued a Certificate of Compliance by the DAR since 1989 because the full transfer of stocks had not happened.) Like Father Bernas in 1989 and the UP Center of Law in 1990, Riedinger also said the SDO “appears to violate the constitutional mandate that ownership of agricultural lands be redistributed to the regular farm workers cultivating them." 3% production share and home lots Under the SDO, Luisita’s farm workers were entitled to two new perks: they were allotted a 3% share in the gross production output of the hacienda, and some were given home lots inside the plantation. The farm workers make clear, however, that these were mandated by law under Section 30 and Section 32 of CARP, not voluntary acts of generosity of the Cojuangcos. The 3% production share never went beyond P1,120 per farm worker per year. The titles of the home lots also have problems, which this report will not get into now. About 5 years after the SDO was implemented, management began to claim that HLI was losing money. The farm workers’ wages plateaued and their work days were cut. Meanwhile, a mall and industrial park were sprouting on the portion of the hacienda closest to McArthur Highway. Conversion—the real plan On September 1, 1995, the Sangguniang Bayan of Tarlac passed a resolution reclassifying 3,290 out of Luisita’s 4,915 hectares from agricultural to commercial, industrial, and residential. The governor of Tarlac province at that time was Margarita “Tingting" Cojuangco, wife of Jose “Peping" Cojuangco, Jr. Out of the 3,290 reclassified hectares, 500 were approved for conversion by the DAR. As land was being converted, the area left for farming grew smaller and smaller. More work days were cut, and wages were practically frozen. Mechanization also reduced the need for manual labor.

Part 1: Hacienda Luisita's past haunts Noynoy's future The issues surrounding Hacienda Luisita are being seen as the first real test of character of presidential hopeful Noynoy Cojuangco Aquino, whose family has owned the land since 1958. Our research shows that the problem began when government lenders obliged the Cojuangcos to distribute the land to small farmers by 1967, a deadline that came and went.

Part 1: Hacienda Luisita's past haunts Noynoy's future The issues surrounding Hacienda Luisita are being seen as the first real test of character of presidential hopeful Noynoy Cojuangco Aquino, whose family has owned the land since 1958. Our research shows that the problem began when government lenders obliged the Cojuangcos to distribute the land to small farmers by 1967, a deadline that came and went.  Part 3: How a worker's strike became the Luisita massacre As Sen. Noynoy Aquino campaigns for the presidency, new attention has been focused on events of five years ago when labor strife on his family's sugar estate left seven dead. This is the third of a series that examines the tortured history of Hacienda Luisita, an issue that would face another Aquino administration.

Part 3: How a worker's strike became the Luisita massacre As Sen. Noynoy Aquino campaigns for the presidency, new attention has been focused on events of five years ago when labor strife on his family's sugar estate left seven dead. This is the third of a series that examines the tortured history of Hacienda Luisita, an issue that would face another Aquino administration.  Part 4: After Luisita massacre, more killings linked to protest After the massacre of 2004, eight more people who were either leaders or supporters of the Luisita strike were murdered in Tarlac. A GMANews.TV investigation reveals that a survivor of one shooting testified in 2005 that Sen. Noynoy Aquino had appealed to him about a "superhighway", which turned out to be the now controversial SCTex.

Part 4: After Luisita massacre, more killings linked to protest After the massacre of 2004, eight more people who were either leaders or supporters of the Luisita strike were murdered in Tarlac. A GMANews.TV investigation reveals that a survivor of one shooting testified in 2005 that Sen. Noynoy Aquino had appealed to him about a "superhighway", which turned out to be the now controversial SCTex.  Part 5: Win or lose, Noynoy has to face Luisita deadlock Since 2006, Hacienda Luisita and its farmer-beneficiaries have been locked in a stalemate after the Supreme Court temporarily stopped the implementation of a government order revoking the stock distribution option of the hacienda. In the fifth and last part of this series, presidential candidate Noynoy Aquino speaks on the range of Luisita-related issues that could hound his administraiton if he wins.

Part 5: Win or lose, Noynoy has to face Luisita deadlock Since 2006, Hacienda Luisita and its farmer-beneficiaries have been locked in a stalemate after the Supreme Court temporarily stopped the implementation of a government order revoking the stock distribution option of the hacienda. In the fifth and last part of this series, presidential candidate Noynoy Aquino speaks on the range of Luisita-related issues that could hound his administraiton if he wins.

Senator Noynoy Aquino’s mother, President Cory Cojuangco Aquino, was accused of including the SDO in her outline for CARP (Presidential Proclamation 131 and Executive Order No. 229, July 22, 1987) so her family could once again avoid distributing Hacienda Luisita to farmers.

Senator Noynoy Aquino’s mother, President Cory Cojuangco Aquino, was accused of including the SDO in her outline for CARP (Presidential Proclamation 131 and Executive Order No. 229, July 22, 1987) so her family could once again avoid distributing Hacienda Luisita to farmers.

(The SDO was a clause in CARP that allowed landowners to give farmers shares of stock in a corporation instead of land. It was abolished in the updated land reform law CARPER, or CARP with Extensions and Revisions, that was passed in August 2009.)

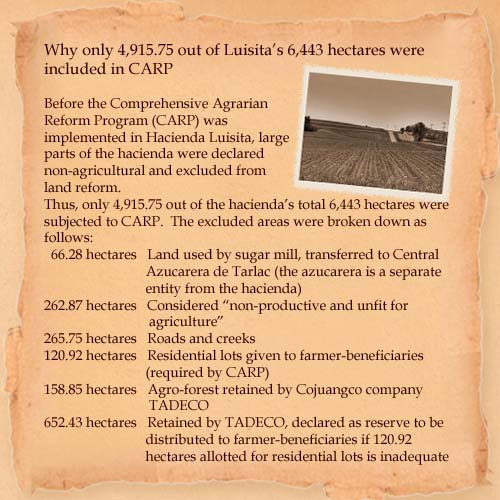

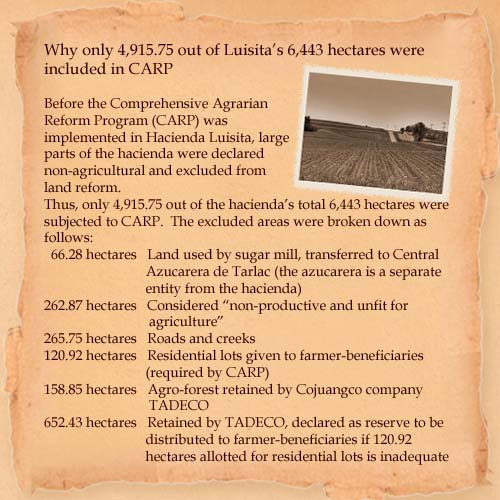

The excluded areas caused the undervaluation of the farm workers’ share in HLI, explained Eduardo Tadem, member of the technical working group of the Presidential Agrarian Reform Council (PARC), in an October 20, 1989 report of the Philippine Daily Inquirer. (In the same report, Tadem said the PARC, which was chaired by President Cory Aquino, had ignored a study of the National Economic Development Authority (NEDA) showing Luisita’s farm workers could earn more with 0.78 hectares of land instead of stocks.) The remaining 4,915.75 hectares that were submitted to CARP were “independently appraised by Asian Appraisal and the Securities and Exchange Commission" at P40,000 per hectare, according to an August 30, 1989 article in the Manila Bulletin written by the Aquino administration’s Solicitor General, Frank Chavez, to defend Luisita’s SDO. The valuation of P40,000 per hectare represents an enormous difference from the valuation of about P500,000 per hectare and P219,000 per hectare respectively for the excluded 120.9 hectares of residential land and 265.7 hectares of land improvements that were retained by the Cojuangcos.

Farmers asked to vote on SDO On May 9, 1989, Luisita’s farm workers were asked to choose between stocks or land in a referendum. The SDO won 92.9% of the vote. A second referendum and information campaign were held on October 14, 1989, and again the SDO won, this time by a 96.75% vote. In his 1992 book A Captive Land: The Politics of Agrarian Reform in the Philippines, London-based development studies expert James Putzel expressed doubt that the farmers understood the choice that was presented to them. “The outcome of the vote was entirely predictable," he wrote. “The balance of power in the country favored families like the Cojuangcos. The problem was not really that the farm workers were denied the right to choose . . . it was rather that [they] were denied an environment that would allow them to identify what their choices were." (Dr. James Putzel did extensive research on agrarian reform in the Philippines between the late 1980s to the early 1990s. He is currently a Professor of Development Studies at the London School of Economics.)

Farmers asked to vote on SDO On May 9, 1989, Luisita’s farm workers were asked to choose between stocks or land in a referendum. The SDO won 92.9% of the vote. A second referendum and information campaign were held on October 14, 1989, and again the SDO won, this time by a 96.75% vote. In his 1992 book A Captive Land: The Politics of Agrarian Reform in the Philippines, London-based development studies expert James Putzel expressed doubt that the farmers understood the choice that was presented to them. “The outcome of the vote was entirely predictable," he wrote. “The balance of power in the country favored families like the Cojuangcos. The problem was not really that the farm workers were denied the right to choose . . . it was rather that [they] were denied an environment that would allow them to identify what their choices were." (Dr. James Putzel did extensive research on agrarian reform in the Philippines between the late 1980s to the early 1990s. He is currently a Professor of Development Studies at the London School of Economics.)

This bred suspicion that the SDO was considered a done deal early on, and the two rounds of voting with the farmers were only organized to give an appearance of transparency. Aquino appointees in charge of DAR Adding to the cloud of doubt was President Aquino’s perceived influence over the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) because she had the power to appoint the department’s head. The Agrarian Reform Secretary who oversaw the farmers’ vote in Luisita in May 1989 was Philip Juico, the husband of Margie Juico, a close friend of President Aquino who also served as her Appointments Secretary. In July 1989, Aquino replaced Phillip Juico with “graft buster" Miriam Defensor-Santiago after Juico’s name was dragged into the Garchitorena land scam.

This bred suspicion that the SDO was considered a done deal early on, and the two rounds of voting with the farmers were only organized to give an appearance of transparency. Aquino appointees in charge of DAR Adding to the cloud of doubt was President Aquino’s perceived influence over the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) because she had the power to appoint the department’s head. The Agrarian Reform Secretary who oversaw the farmers’ vote in Luisita in May 1989 was Philip Juico, the husband of Margie Juico, a close friend of President Aquino who also served as her Appointments Secretary. In July 1989, Aquino replaced Phillip Juico with “graft buster" Miriam Defensor-Santiago after Juico’s name was dragged into the Garchitorena land scam.

Very early into her role, Santiago, a former judge, told the media that there were “serious flaws in the law against which I am powerless" (Philippine Daily Inquirer, July 21, 1989). Santiago ended up giving Luisita’s SDO the go-signal in November 1989. Two months later, Aquino replaced Santiago. Many years later, Santiago said Aquino removed her because of something she said about Luisita.

Luisita’s SDO agreement spelled out a 30-year schedule for transferring stock to the farm workers: “At the end of each fiscal year, for a period of 30 years, the SECOND PARTY (HLI) shall arrange with the FIRST PARTY (TADECO) the acquisition and distribution to the THIRD PARTY (farm workers) on the basis of number of days worked and at no cost to them of one-thirtieth (1/30) of 118,391,976.85 shares of the capital stock of the SECOND PARTY (HLI) that are presently owned and held by the FIRST PARTY (TADECO), until such time as the entire block of 118,391,976.85 shares shall have been completely acquired and distributed to the THIRD PARTY (farm workers)." The impact of this provision was far-reaching.

“The hacienda tenants voluntarily agreed to give up land distribution for shares of stock of the corporation", and have enjoyed the fruits of their “wise decision". (Philippine Daily Inquirer, February 25, 2007) “The only reason we got [into Luisita] to begin with was the people asked for us, or we were acceptable to them. There was a labor problem sometime in the 1950s, when I wasn’t still around." (Philippine Daily Inquirer, September 13, 2009) On the farmers’ plea to have Luisita’s SDO contract revoked so land can be distributed: “The Constitution talks of inviolability of contracts." (Philippine Daily Inquirer, November 10, 2009) “We want to leave only when we have formulated the plan on how they could pay the debts of the corporate farm. When that has been cleared, then we could bid goodbye [to Luisita management]." (Manila Times, November 13, 2009) “The problems descending a sunset industry like the sugar industry were exploited by quarters outside the hacienda. The net result is that the people who had jobs from 1958-2004 have lost their jobs." (Statement emailed to GMANews.TV on December 7, 2009) “We are working for the restoration of jobs. Those who are forcing us to speak on this matter are not after the welfare of my former constituents, but to advance their propaganda aims." (Statement emailed to GMANews.TV on December 7, 2009)

Tags: haciendaluisita, noynoyaquino

Find out your candidates' profile

Find the latest news

Find out individual candidate platforms

Choose your candidates and print out your selection.

Voter Demographics

More Videos

Most Popular